A couple of weeks ago, a friend and I journeyed South to check out a neighborhood we'd never seen--Historic

Pullman. I remember reading in high school about the experimental company town founded by Georege Pullman for the employees of his Pullman Palace Car Company.

Pullman developed the sleeping car. In the 1880's, as heavy industry, in Chicago and around the world, was exploding and laissez faire capitalism was leading to increasingly horrific working conditions, Pullman came up with an idea that he thought would mollify the concerns of labor organizers and simultaneously encourage more productive workers—the creation of “the world’s most perfect town.”

Although our modern cynicism might immediately bristle at such a claim, the fundamentals of

Pullman initially seemed sound—provide worker’s with clean, safe living arrangements, an entire community complete with stores, schools and recreational facilities, and the workers will come to work healthier and happier. Everybody wins. Except everyone can’t win, when one man wants to make a big profit.

(Notice the green trim on this Pullman House's front stoop)

(Notice the green trim on this Pullman House's front stoop)

Pullman chose a formerly swampy area near the

Calumet River to build his factory and his town.

He built a hotel to host dignitaries, the Hotel Florence (named after his daughter) and a railroad was constructed to link

Pullman with downtown

Chicago. There were boarding houses for single workers, worker’s cottages for families, and nicer homes for managers and executives. The houses were equipped with state of the art facilities such as indoor plumbing. All of the homes and stores were owned by

Pullman., and

Pullman, himself, insisted on making at least a 6% profit on the town’s operations including rent each year. This is where the trouble begins. Just as we saw in

Devil in the White City, 1893 was not a good year for the American economy.

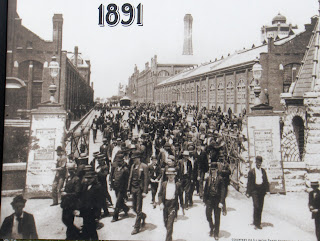

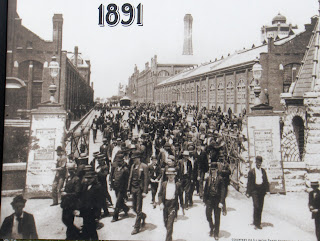

The demand for sleeping cars decreased, and concurrently so did the number of jobs and the size of the wages of

Pullman’s workers. What didn’t decrease, was rent in

Pullman. This caused one of the most significant workers’ strikes of the 19

th century—Eugene Debs, head of the American Railway Union, became involved and as many as 250,000 workers struck nationwide. Eventually President Grover Cleveland sent in the National Guard to end the strike. A few years later after

Pullman’s death, “the world’s most perfect town” was declared a monopoly by the Illinois Supreme Court, and the homes and businesses were sold off to private owners.

Today the area is a National Historic District, which means the owners of the former worker’s cottages, executive homes and boarding houses must comply with certain guidelines for the upkeep and renovation of their homes. For example, the officially company paint colors were a light green, a slightly darker green and a red, and these colors are a staple feature of many Pullman exteriors today. We went to Pullman on one of the special days each year where several of the residents open their homes to urban snoops, err…explorers, who are interested in seeing the interiors of these historic houses. It was really interesting to see the way modern Chicago families had repurposed the interiors of these homes, while maintaining the integrity of them from the outside. Some of the owners had completely gutted the original houses to suit their needs and tastes, while in others you could wind around the tiny hallways and small doorways of the Pullman era. I liked these homes the best—the ghosts of old Chicago seemed really palpable in these small oddly shaped rooms, rooms in many ways resistant to our contemporary sense of needs. The residents of Pullman are extremely proud of their community’s history and they have really made a tremendous effort to preserve and reconstruct the details of its unique history. For example, the Pullman Factory Clock tower which lorded over Pullman for a century was burned to the ground by arson in the late 1990’s and the Pullman preservation group raised millions for its reconstruction. The clock now looms over the community again, even though the factory remains completely unoccupied. Its brick walls surround hallow spaces with dirt floors. An eerie silence now inhabits a place that once clamored—with the din of industry and the call for better working conditions. I was struck as I

Today the area is a National Historic District, which means the owners of the former worker’s cottages, executive homes and boarding houses must comply with certain guidelines for the upkeep and renovation of their homes. For example, the officially company paint colors were a light green, a slightly darker green and a red, and these colors are a staple feature of many Pullman exteriors today. We went to Pullman on one of the special days each year where several of the residents open their homes to urban snoops, err…explorers, who are interested in seeing the interiors of these historic houses. It was really interesting to see the way modern Chicago families had repurposed the interiors of these homes, while maintaining the integrity of them from the outside. Some of the owners had completely gutted the original houses to suit their needs and tastes, while in others you could wind around the tiny hallways and small doorways of the Pullman era. I liked these homes the best—the ghosts of old Chicago seemed really palpable in these small oddly shaped rooms, rooms in many ways resistant to our contemporary sense of needs. The residents of Pullman are extremely proud of their community’s history and they have really made a tremendous effort to preserve and reconstruct the details of its unique history. For example, the Pullman Factory Clock tower which lorded over Pullman for a century was burned to the ground by arson in the late 1990’s and the Pullman preservation group raised millions for its reconstruction. The clock now looms over the community again, even though the factory remains completely unoccupied. Its brick walls surround hallow spaces with dirt floors. An eerie silence now inhabits a place that once clamored—with the din of industry and the call for better working conditions. I was struck as I  wandered the streets of modern Pullman by what it must be like to live in a place that was conceived in such an unusual way. I imagined the pride of people walking into their shiny new homes on their first day of work at the factories; I imagined the agony of a family trying to find the money for next month’s rent. I imagined walking by the home of the executives and seeing the dignitaries smoking cigars on the porch of the Hotel Florence (this place is supposedly haunted—But it’s a sore point tour guides about it!) the year of the Great Exhibition. I imagined listening to Eugene Debs in the park and grappling the unique conflicts of striking against both your employer and your home.

wandered the streets of modern Pullman by what it must be like to live in a place that was conceived in such an unusual way. I imagined the pride of people walking into their shiny new homes on their first day of work at the factories; I imagined the agony of a family trying to find the money for next month’s rent. I imagined walking by the home of the executives and seeing the dignitaries smoking cigars on the porch of the Hotel Florence (this place is supposedly haunted—But it’s a sore point tour guides about it!) the year of the Great Exhibition. I imagined listening to Eugene Debs in the park and grappling the unique conflicts of striking against both your employer and your home.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend and I journeyed South to check out a neighborhood we'd never seen--Historic Pullman. I remember reading in high school about the experimental company town founded by Georege Pullman for the employees of his Pullman Palace Car Company.

A couple of weeks ago, a friend and I journeyed South to check out a neighborhood we'd never seen--Historic Pullman. I remember reading in high school about the experimental company town founded by Georege Pullman for the employees of his Pullman Palace Car Company.  (Notice the green trim on this Pullman House's front stoop)

(Notice the green trim on this Pullman House's front stoop)  Today the area is a National Historic District, which means the owners of the former worker’s cottages, executive homes and boarding houses must comply with certain guidelines for the upkeep and renovation of their homes. For example, the officially company paint colors were a light green, a slightly darker green and a red, and these colors are a staple feature of many

Today the area is a National Historic District, which means the owners of the former worker’s cottages, executive homes and boarding houses must comply with certain guidelines for the upkeep and renovation of their homes. For example, the officially company paint colors were a light green, a slightly darker green and a red, and these colors are a staple feature of many  wandered the streets of modern

wandered the streets of modern

No comments:

Post a Comment